Published: January 7, 2024 | 7 mins read

Are Digestive Disorders Causing Your Kidney Stones?

Some doctors would blame “digestive disorders” for their patients’ kidney stones. And the common culprits you’ll hear are inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and chronic pancreatitis.

Well, anything that happens in the digestive system will impact the absorption of nutrients and electrolytes. And since the primary cause of kidney stones is DIET, the risk of forming stones could be affected in some ways.

However, do digestive disorders REALLY increase your stone risk?

Let’s dig deeper.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE (IBD) AND KIDNEY STONES

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to disorders that cause chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The two most common forms are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Please note that IBD should not be confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBS has similar symptoms, but it does not cause damage to the digestive tract.

More than 10 million, or <1% of the global population, are suffering from IBD. Surprisingly, ~3 million of these are US adults (1.3% of the US population). This was according to the latest data (2015) from Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Unfortunately, even with millions of people suffering from this condition, the real cause of IBD remains a mystery. However, some link it to an impaired immune response to intestinal bacteria and other microorganisms. But, we have our sneaking suspicion that it’s all related to the foods we eat.

But How Does It Relate To Kidney Stones?

There are not many studies focusing on this topic at present. However, researchers analyzed the available data from 126 stone-formers with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis to check this correlation.

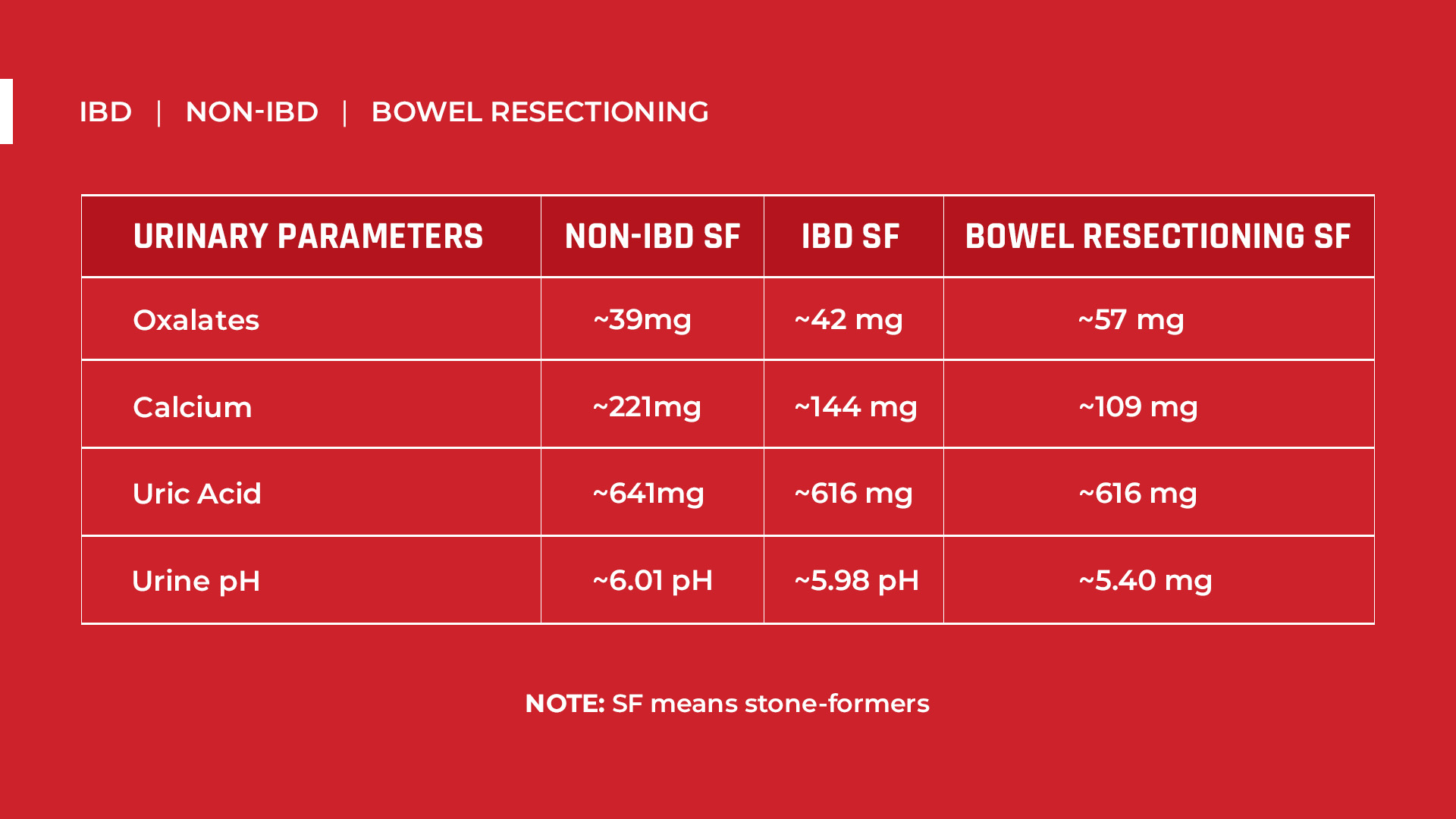

There’s only a slight rise in the 24-hour urinary oxalates (~42mg) in IBD patients compared to stone-formers with no IBD (~39mg). However, it largely increased in patients with small bowel resectioning (~57mg). These patients had a part of their intestine (such as the duodenum, jejunum, or ileum) removed in an effort to combat their IBD.

If you’ve read our blog on Hyperoxaluria, you’ll remember that urinary oxalate excretion of more than 25mg per day is already high.

Calcium excretion is also lower in IBD patients (~144mg) than in non-IBD patients (~221mg). And urinary calcium decreased even more in patients who had both colon and small bowel resectioning (~109mg).

Calcium levels <200 mg/L in 24-hour urine are still normal. And this will not cause kidney stones unless oxalates are present. Read our blog about Hypercalciuria to understand this better.

Stone-formers with IBD have slightly more acidic urine (~5.98 pH) than the non-IBD stone formers (~6.01 pH). And urine pH is even lower for IBD patients with colon resectioning (~5.40 pH). This is a critical consideration because stones usually form at pH between 4.5 and 5.5.

Uric acid excretion is lower in all IBD patients, with or without surgery (~616mg), compared to non-IBD (~641mg).

Putting it all together, this data suggests that IBD (Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis) may affect stone risk concerning oxalates and urine pH. However, no research has yet confirmed the mechanisms of how IBD affects these factors, nor do we find the differences between IBD and non-IBD populations that significant.

The only significant differences in the data came from individuals who had bowel resectioning surgery. The bad news is many IBD patients resort to surgeries. That said, around 20% of ulcerative colitis patients and up to 80% of Crohn’s disease patients undergo operations. Regardless, if the patients choose not to undergo surgery, the risk for kidney stones is no different from the general population.

Now that we have IBD factors understood, let’s move on to Chronic Pancreatitis to understand what (if any) role this disorder plays in kidney stone risk.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS AND KIDNEY STONES

Chronic pancreatitis is an inflammatory disorder in the pancreas that destroys the exocrine (vital in digestion) and endocrine parenchyma (excretes insulin, etc., directly to the bloodstream).

This happens when the pancreas degenerates or shrinks (atrophy), or the tissues are scarred (fibrosis).

The annual incidence of chronic pancreatitis in the US is about 5 to 8 per 100,000 adults (<1% of the US population or about 80,000 people per year). It is said to be 4.5 times more common in men, and the average onset age is 62 years.

Alcohol consumption is the most common cause (70%–80%) of chronic pancreatitis worldwide. Although, only <10% of alcoholics are known to develop this condition.

Alcohol (pure ethanol) intake is already abusive if regular intake is greater than 50g (1.7 fl. oz.) in men and 25g (0.85 fl. oz.) per day in women.

In the US, the “standard drink” or “alcohol drink equivalent” is any drink with 14 g (0.6 fl. oz.) of pure ethanol. This could be found in a regular beer (12 oz.) with 5% alcohol by volume (alc/vol) or 5 ounce of table wine with 12% alc/vol.

The US Dietary Guidelines 7 only recommends 2 drinks (or less) for men, while 1 drink (or less) for women. Consuming 3-4 alcoholic drinks (50 g ethanol) is already abusive.

But How Does It Relate To Kidney Stones?

Honestly, no studies have yet reported a direct correlation between chronic pancreatitis and kidney stones. Chronic pancreatitis is instead indirectly related to oxalate absorption.

The mechanism looks like this: Fat malabsorption is the most dominant result of exocrine (digestive-related) insufficiency. Unabsorbed bile acids and fatty acids will bind with calcium in the gut. Thus, there would be limited calcium ions to bind with oxalates in the gut. This is believed to result in more unbound oxalates absorbed in the stomach and the colon. When absorption increases, urinary oxalate excretion also increases, leading to higher stone risk.

However, the gut absorbs calcium faster (about 2-3 hours) than oxalates (several days).So it is not possible for them to bind perfectly in there in the first place. In short, the mechanism of how fat malabsorption really leads to more oxalate absorption still requires more scrutiny.

Researchers have not conducted many studies on this subject yet, just like with IBD. Nevertheless, in a study involving 48 chronic pancreatitis patients, 23% were seen with hyperoxaluria (~52mg/g UOCR). Hyperoxaluria means urinary oxalate/creatinine ratio (UOCR) of >32mg/g. Again, it also means urinary oxalate excretion of >25mg per day.

CONCLUSION

Digestive disorders play some part in kidney stone incidence, but they are not the main reasons. We believe that the foods you eat remain the primary cause for kidney stones. After all, these digestive disorders can be products of inappropriate dietary patterns too (ex. Alcohol abuse).

So, if you want to combat kidney stones, the best route is to change your diet. HINT: changing your diet will also likely completely eliminate any digestive tract disorders.

Here are the best resources to help you achieve your goal:

- Diet’s Impact on Kidney Stones Blog

- Kidney Stone Diet Prevention Course Inside the Stone Relief Community

- One-On-One Diet Coaching

References

- What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)?

- What is IBD?

- IBD Statistics 2022: Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis

- Prevalence of IBD

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Urine stone risk factors in nephrolithiasis patients with and without bowel disease

- Hyperoxaluria

- Hypercalciuria

- The effect of pH on the risk of calcium oxalate crystallization in urine

- Surgery for inflammatory bowel disease in the era of laparoscopy

- Chronic Pancreatitis

- Association between chronic pancreatitis and urolithiasis: A population-based cohort study

- Enteric hyperoxaluria in chronic pancreatitis

- The Basics: Defining How Much Alcohol is Too Much

- Mechanisms of intestinal calcium absorption

Like low stomach acid?

Hi Heather!

Low stomach acid doesn’t directly impact kidney stone risk. However, it may impact how nutrients are absorbed in your gut, which can increase stone risk over time. Do you suffer from this condition?

Yes I believe I do

The first thing you need to do is find out what is causing your low stomach acid exactly. So, we suggest that you undergo a diagnosis first. Then, from there, if you already know the exact cause of your low stomach acid, we can make the right dietary changes based on your specific health condition.