Published: December 17, 2023 | 5 mins read

Low Citrate Intake Can Lead To Kidney Stones

Let’s repeat that title. Low citrate intake can lead to kidney stones. But, what exactly is citrate?

Simply, citrate is a compound mainly derived from citric acid. And the main sources of citric acid are the foods we eat (e.g. citrus fruits). Citrate is also metabolized through a complex process in the cells called citric acid cycle (also called Krebs cycle).

Citrate is an important component of urine chemistry. In 24-hour urine test, citrate levels are measured to check if our kidneys handle the acids in our body well.

Also, it is used to assess whether a person is at risk of kidney stones.

HOW DO CITRATE LEVELS AFFECT STONE RISK?

Low urinary citrate is also known as hypocitraturia. This condition impacts roughly 20-60% of stone formers and is a significant risk factor for kidney stones.

Hypocitraturia occurs when concentration levels of urinary citrate are less than 320mg/L (1.67 milliosmoles) for adults. Meaning over the course of an average day, adults should pass around 643 mg in 2 liters of urine.

But, how does this translate into a risk for kidney stones?

Calcium-based Stones

Citrate binds with calcium ions in the urine. The binding of calcium with citrate makes calcium ions unavailable to bind with other ions like oxalate or phosphate which would eventually form either calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate kidney stones.

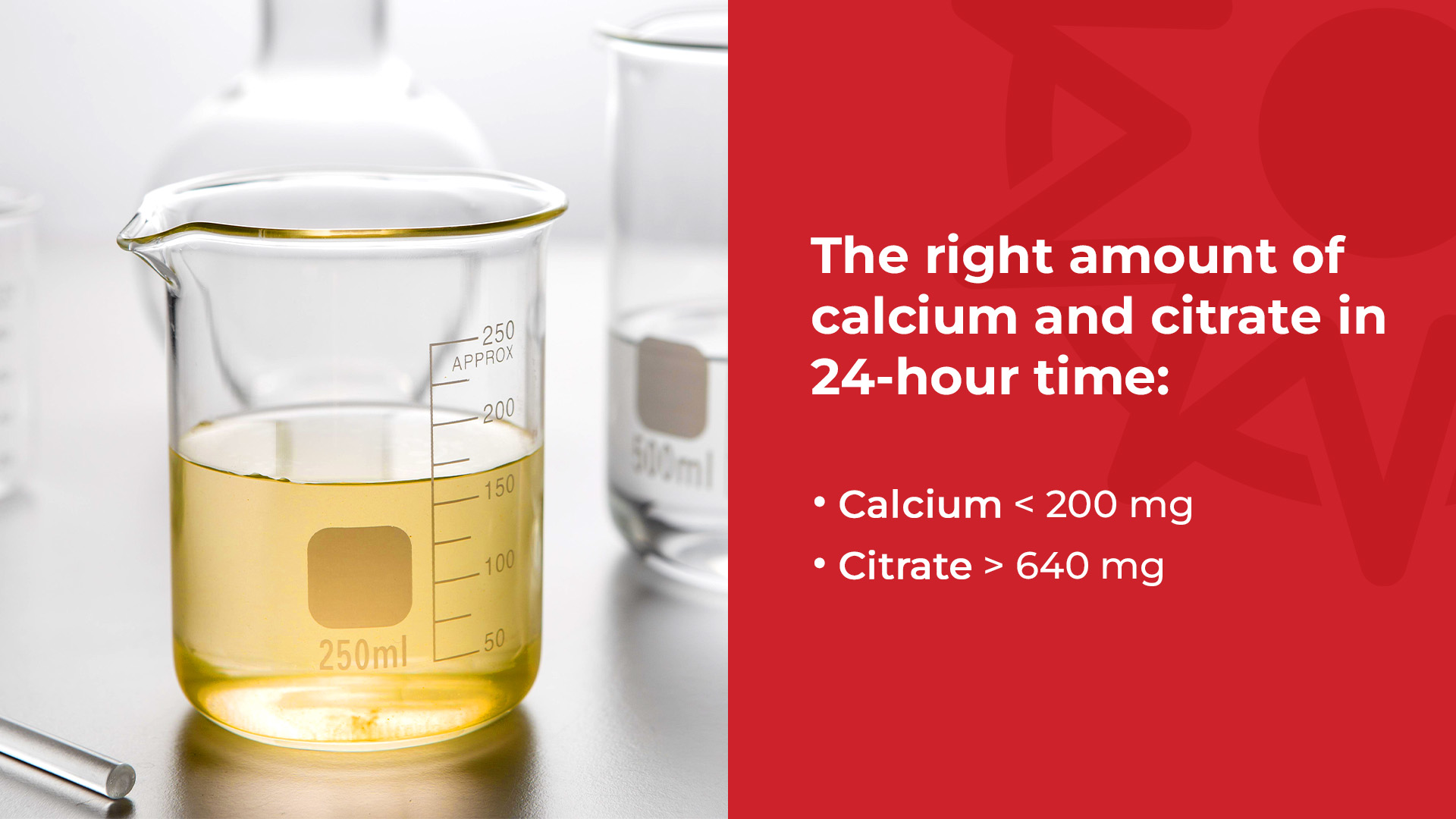

Urinary calcium should be <200 mg (or <100 mg/L), while urinary citrate should be around 320 mg/L. This is the ideal proportion of calcium and citrate in 24-hour urine panel for individuals with kidney stones.

So, if you have hypocitraturia (citrate levels <320 mg/L urine), there is more opportunity for calcium to bind with either oxalate or phosphate to eventually form kidney stones.

Additionally, citrate enhances the activity of a protein called Tamm-Horsfall protein that helps prevent the further growth of calcium-oxalate crystals.

Uric Acid Stones

Citrate may also help reduce the risk of uric acid kidney stones. This is because citrate is metabolized into bicarbonate. This alkaline substance neutralizes acids in the body and increases urine pH. Low urine pH (<5.5) is where uric acid stones form. So, when you shift urine pH toward neutral (6.5 – 7.5), uric acid kidney stones can no longer form.

A long-term study involving 19 patients with hyperuricosuria (excess uric acid in the urine) supported this claim. Around 7.4 to 9.9g (60-80 mEq) of potassium citrate was given to the subjects. This contains about 2.4 to 3.3g citrate.

By the end of the control, urinary pH rose by 0.55 to 0.85, reaching the high normal range 6.5 to 7.0. Urinary citrate levels also rose to about 249 to 402m0g per day. Another study was conducted among 89 patients given potassium citrate for 1 to 4 1/3 years. It also showed the same significant increase in urinary pH, citrate, and potassium.

WHAT CAUSES HYPOCITRATURIA?

More often than not, low citrate can be linked to diet. However, this can be a confusing mess as most of the advice you receive from the modern medical establishment will point you in the wrong direction (i.e. less meat, more fruit and even more vegetables).

Additionally, a diet high in sodium (> 2.3g/day) can also lead to hypocitraturia. This is because citrate reabsorption in the kidneys is affected by sodium levels.

Dicarboxylate transporter (NaDC-1), the most dominant transport protein for citrate, is sodium-dependent. This protein is known as a co-transporter of both sodium and citrate. So when urine sodium is high, the NaDC protein becomes more active and reabsorbs more sodium and citrate from the urine.

On the other hand, when citrate levels are high, NaDC-1 is less active, so less citrate is reabsorbed from the urine. This increases urinary citrate and reduces the risk of kidney stone formation.

Metabolic disorders such as distal renal tubular acidosis (dRTA) can also lead to low urinary citrate. This condition occurs when the renal tubules (the basic unit of the kidney’s functional part) fail to acidify the urine properly. This causes acid buildup, which increases citrate reabsorption in the kidney. But, the exact mechanism of how it happens is not yet fully understood.

Low blood potassium (hypokalemia) is also a potential cause. Hypokalemia increases the acid load in the blood, which triggers the NaDC protein to reabsorb more citrate to help buffer the body’s acidity.

Chronic diarrhea can also lead to hypocitraturia because of metabolic acidosis (which causes excess acid in the blood). Metabolic acidosis also causes acidic urine, which isn’t ideal for citrate transport.

Lastly, medications such as thiazide diuretics and ACE inhibitors (both for hypertension) can also lower urinary citrate.

HOW TO PREVENT LOW CITRATE LEVELS

Diet plays a very important role in avoiding hypocitraturia, unless you have underlying disorders. Actually, diet is the major player in your overall kidney stone problem. To increase your urinary citrate levels, you need to eat more foods high in citric acid. But you have to be cautious on this part, some foods that are good sources of citrate can be high in oxalates. This will set you up for failure in the long run. Nevertheless, some low oxalate, high citric acid foods you can choose are the following:

- Dairy products like milk, cheese, and yogurt

- Fruits like lemons, apples, bananas, and grapes

Savoring these foods are just one aspect of your kidney stone prevention. If you’re serious about putting an end to your kidney stones, checkout Coaching Program today.

References

- 24-Hour Urine Testing for Nephrolithiasis: Interpretation Guideline

- Hypocitraturia: Pathophysiology and Medical Management

- Urinary citrate and renal stone disease: the preventive role of alkali citrate treatment

- Successful treatment of hyperuricosuric calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis with potassium citrate

- Hypocitraturia and its role in renal stone disease

- Sodium in Your Diet

- Hypocitraturia Despite Potassium Citrate Tablet Supplementation

I struggle to enjoy my diet anymore on low oxalate

What are you eating on your low-oxalate diet, Stephen?

Rice, chicken, garlic bread.

Potatoes is a huge loss for my diet, regular pasta too. Tinned tomatoes is one I used to use a lot too.

It’s so restrictive low oxalate.

Oxalates are hardly everywhere on plant foods and it’s cumulative. That’s why for some people, even a low-oxalate diet is not enough to solve kidney stones.

My urologist nurse always stresses lemon or citrus in my diet to prevent stones

That’s great!